第4号 特集:構築4の庭へ Imagining the Gardens of Building Mode 4 走向构筑4之庭

アヴァン・エディブル・ガーデニング──クリスティン・レイノルズと話す、米国における都市農園の政治

マシュー・ムレーン【東京大学東京カレッジ博士研究員】

Avant Edible Gardening: Speaking with Kristin Reynolds on the Politics of Urban Farmingin the United StatesMatthew Mullane【PhD, University of Tokyo, Tokyo College 】

可食用的先锋园艺──对话克里斯汀・雷诺兹,美国都市中的农场政治

いつ農園farmは庭園gardenになるのか? 英語では、「farm」と「garden」はしばしば明確に区別される。農園は食料を生産する場であり、庭園は哲学的ポテンシャルを持つ人造の空間と理解される。庭園はその文化の価値観や文明の展望を体現する小宇宙である。そのため美術史や建築史の研究者は、日本やフランス、イギリスの、農園ではなく庭園を研究することがより一般的である。しかし、農園もまた、伝統的な庭園と同じように文化を表象することができる。米国の都市農園以上に、このことを顕著に表す場所はない。人種差別、経済的不平等、社会正義、医療アクセス、政府の責任についての異なる定義、そしてこの国のハイテク産業のたえず大きくなる影響等の問題に形づけられながら、多くの仕方で、都市農園は現代アメリカ生活の小宇宙となっているのだ。

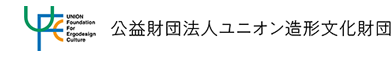

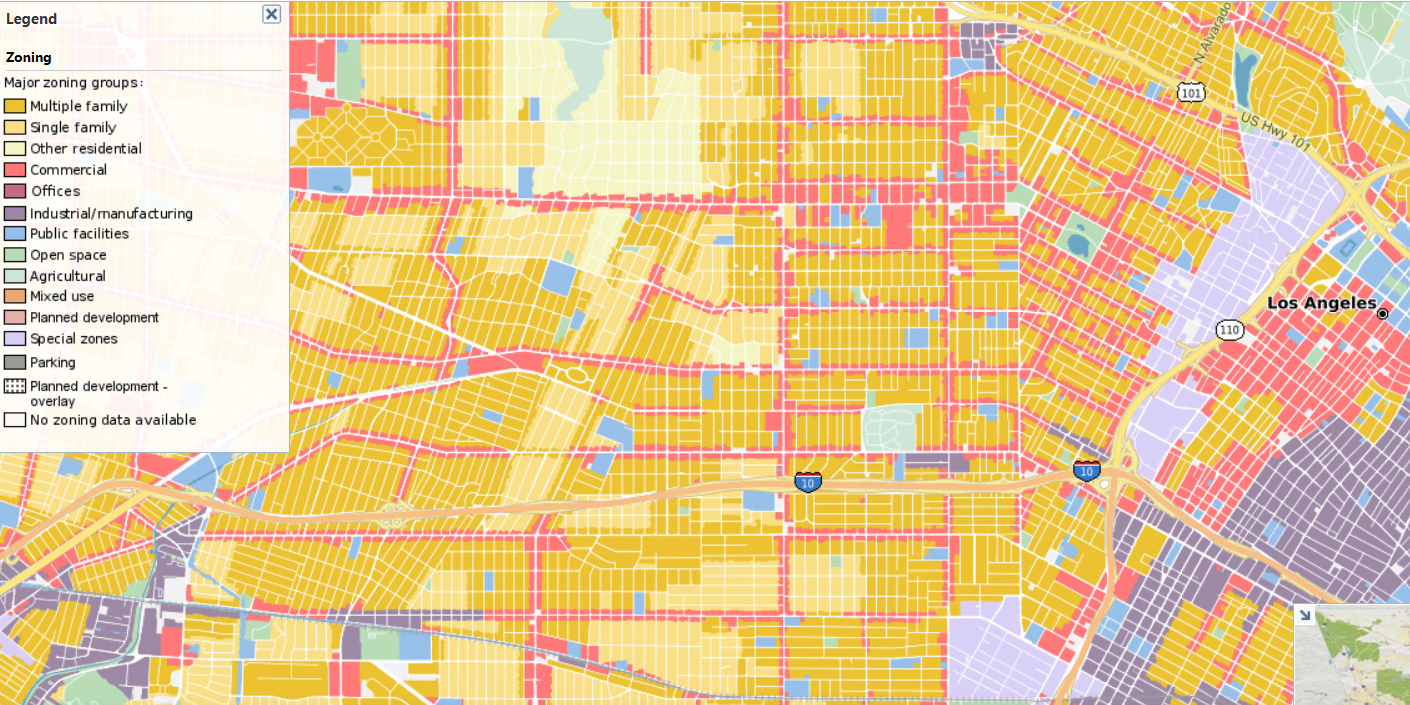

日本の都会では、小さな農地は驚くほどよく見られる光景だ。初めて東京を訪れる人が終わりなきコンクリートの広がりを予期していたなら、マンションの隣に田んぼがあることに驚くかもしれない。私はかつて練馬区に住んでいたことがあるが、近所には一区画の畑と農家が管理する「自動販売機」があり、数百円で大根やキャベツを購入することができた。日本においてこのように生活と農地が密接しているのは、行政が、住宅、農業、商業、工業をさまざまなパターンで共存させるシステムである複合用途ゾーニングを受け入れているためである。しかし米国では、ほとんどの都市が、排他的な単一用途ゾーニングによって深く形成されてきた。単一用途ゾーニングは、住宅地を商業や工業による悪影響から切り離す手段として説明されることが多いが、それは富裕層と貧困層、白人と有色人種を分離するための道具として長い間使われてきたのである。都市の近郊や都市の内部における農業空間の不在は、都市から食料や緑を枯渇させるだけではない。それは人種的・経済的に人々を分断しようとする、米国の過去と現在の努力が生んだ空間的人工物なのである。

練馬区の自動販売機

photo by André Viljoen and Katrin Bohn, 2018.

戸建て用地と商業用地の線引きを示すロサンゼルスのゾーニングマップ

Source: https://www.propertyshark.com/mason/text/Zoning-Zimas-LA.html

このような歴史に照らせば、米国における都市農園が政治性を帯びていることは間違いない。自分自身の食料を生産する能力はつねに保証されてきたわけではない。先住民やマイノリティの人々は、強制的に土地から追い出され、排他的な金融プログラムによって土地へのアクセスを拒否され、土地を知るための認識論epistemologiesは抹消されてきたのだ。都市農業とはおそらく、食料生産である以上に、この歴史と関わり、そこから新たなコミュニティを築くための手段である。今日では、米国における農園排除の多くの異なる歴史が、同じように多くの包摂の実験を生んでいる。そこには、私有地や裏庭での小規模な農園、食料生産と学生へのアウトリーチの両方に取り組むコミュニティ農園(レッド・フック・ファームズ、ニューヨークシティ)、先住民族の農業のやり方を再活性化する試み(サン・ザビエル協同農園、アリゾナ州)、急成長する都市農園を援助するネットワーク(ブラック・ファーマー・ファンド、ニューヨーク州)、都市全域の奨励プログラム(ロサンゼルス郡都市農業奨励ゾーンプログラム)が含まれる。

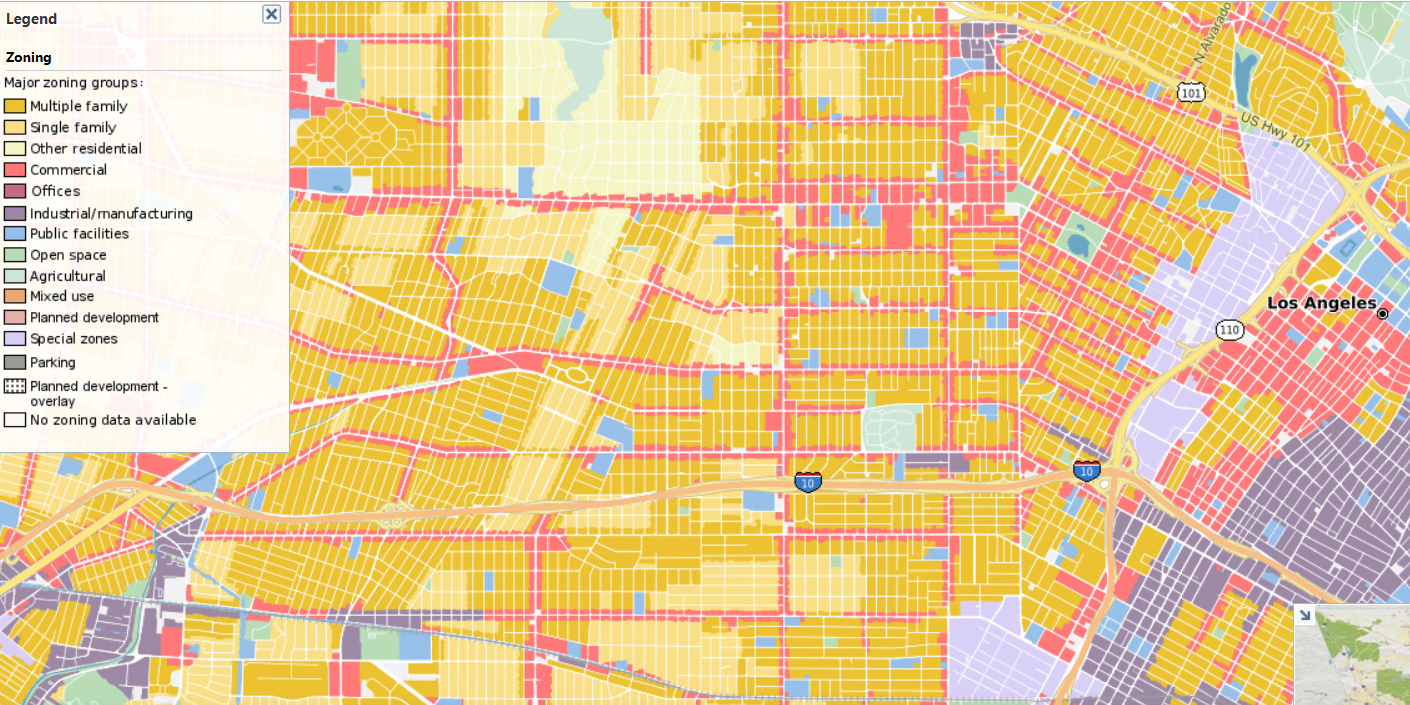

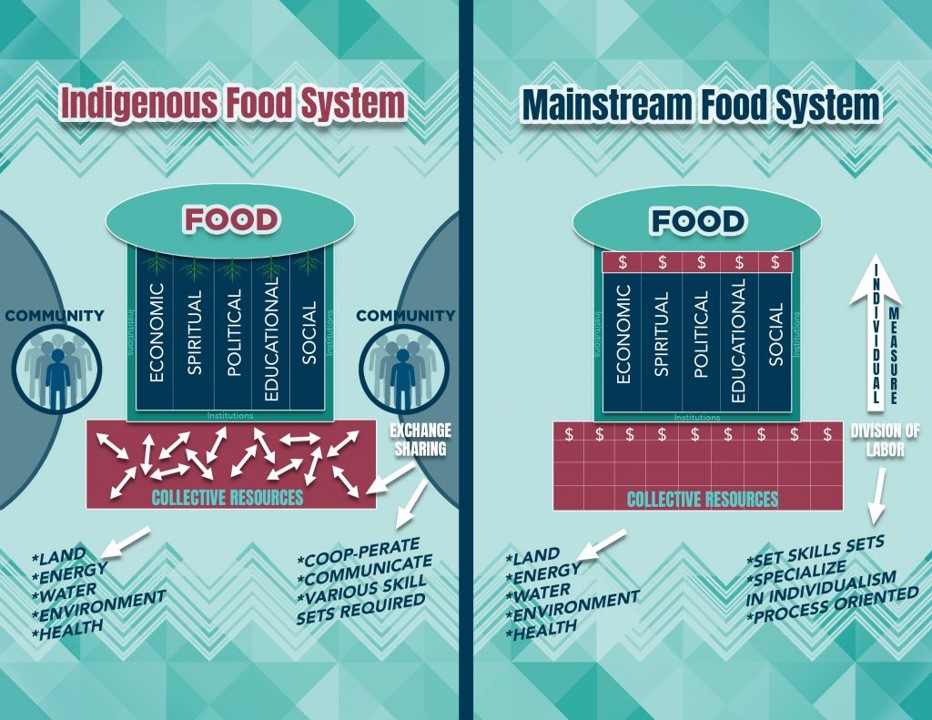

では、こうした農園やプログラムは、生環境構築史と「構築4」に向けた私たちの探索とどう関係するのだろうか。HBHのダイアグラムと曲線を描く進歩の矢印を見ながら、私は「構築4」とは、後ろを振り返ることによって前進する方法であるとしばしば考えてきた。都市農園においてこの振り返るという行為は、国家の暴力的な過去を学び、かつそれに応答し、すでに抹消されてしまった自然を知るための方法を理解することによって実践されている。しかしそれは、これらの農園がノスタルジックであるということを意味しない。 むしろこれらの農園は、資本主義的工業化の破壊的な謀略のただなかで失われたものを蘇らせ、それを養い、未来にそれが育つことを願っているのだ。アメリカにおける先住民の思想家たちによって行われた最近の仕事は、このアプローチを例証している。ファースト・ネイションズ・ディベロップメント・インスティテュート(First Nations Development Institute)のプログラム・ディレクターであるア=デイ・ロメロ=ブリオネス(A-dae Romero-Briones )は、自然に対する私たちの理解を「脱植民地化」することに基づく「再生」農業を呼びかけている。彼女は、「再生という概念の核心には、私たちを環境の破壊と悪化に至らしめたつまずきのいくつかを更新し、正す必要がある」と主張している。

ア=デイ・ロメロ=ブリオネス「先住民とメインストリームのフードシステムを比較する」

From A-dae Romero-Briones, “Fighting for the taste buds of our children,” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, volume 9, supplement 2 (2019), 37.

米国における都市農園とその「現在のつまずき」の可能性について学ぶために、ニューヨークシティで仕事をする研究者/活動家であるクリスティン・レイノルズ教授に話を聞いた。2016年、レイノルズはネヴィン・コーエンと共著で『ケールを越えて──ニューヨークシティにおける都市農業と社会正義アクティビズム』(Beyond the Kale: Urban Agriculture and Social Justice in New York City, University of Georgia Press, 2016)を出版した★1。この本は、都市農園がコミュニティ形成と社会変革のハイパー・ローカルなプラットフォームのための手段となりえることを理解する方法に関わる。レイノルズ教授と私は、都市農業の研究方法、都市農園の政治的両義性、そして新しいテクノロジーがもたらす都市農業の未来について語った。

■インタビュー

クリスティン・レイノルズ教授

マシュー・ムレーン──レイノルズ教授、このたびはインタビューの時間を割いてくださりありがとうございます。最初に、なぜ都市農業のフィールドに進まれたのか、その背景を少し教えていただけますか?

クリスティン・レイノルズ──私は社会正義の理由から都市農業に関心を持ち始めました。まずカリフォルニアで、カリフォルニア大学デーヴィス校での大学院での研究と、小規模で資源の限られた農家を対象にした「UCスモール・ファーム・プログラム」を結びつけることから始めたんです。そのあとニューヨークのニュースクールに移り、さまざまなプロジェクトに関わることになりました。そのなかには、最終的に同僚のネヴィン・コーエンとの共著『ケールを越えて』につながったプロジェクト、ファイヴ・ボロー・ファームがあります。私はつねに、自分が住んでいる場所における都市農業コミュニティに関わり、また関心を持ってきました★2。 2000年代初頭にコミュニティ農園が花開いたとき、私はいまだ正当に扱われていない農業があることを理解するようになりました。都市における農園です。この観察は、米国でフード・ジャスティス運動が始まった時期と重なっていました。

クリスティン・レイノルズ+ネヴィン・コーエン『ケールを越えて——ニューヨークシティにおける都市農業と社会正義アクティビズム』

Beyond the Kale: Urban Agriculture and Social Justice Activism in New York City (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2016)

この文脈において私は、ボランティアと研究者という私の二重の経験が重要だと考えています。都市における耕作者とともにそのコミュニティに身を置くことで、私はただパラシュートでやってきて情報を集めて帰るのではなく、倫理的な責任を感じるのです。私の研究では、都市農園は白人が主導する活動であるという広まりつつあるステレオタイプに対抗したいと考えています。なぜなら、シンプルにそれは事実ではないからです。ニューヨークシティでの仕事を通じて、都市農園を成功させている多くの女性や有色の人々 people of color を知るようになりました。『ケールを越えて』で取り上げたのは、そうしたリーダーたちの一部です。彼・彼女らは都市農業を食料生産以上の方法で利用しています。つまり、自分たちの農園と庭園を、そのコミュニティの環境における非常に具体的な社会正義の問題を明確にし、対処するために使用しているのです。

ロブ・スティーブンソン、ユナイテッド・コミュニティ・センターズ・ファーム、ブルックリン、ニューヨークシティ、2011年

ロブ・スティーブンソン、キュリナリー・キッズ・ガーデン(子供の台所庭園)、クイーンズ、ニューヨークシティ、2011年

ロブ・スティーブンソン、ヘルズ・キッチン屋上農園、マンハッタン、ニューヨークシティ、2011年

ムレーン──このインタビューを読む日本の読者に向けて、アメリカにおける食の不平等の問題について簡単に説明していただけませんか。日本とはかなり異なる状況があると思います。あなたが研究された都市農園においては、どのような社会正義の問題に対する応答がなされていたのでしょうか?

レイノルズ──その質問に対する回答は、もちろん複雑です。著名な環境正義学者であるモニカ・ホワイト博士が彼女の著書(特に『フリーダム・ファーマーズ』(Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement (Justice, Power, and Politics) , University of North Carolina Press, 2019)で示したように、歴史的には奴隷制度とポスト奴隷制度の現実が、一部のアフリカ系アメリカ人の人々の農業に対する見方に深く影響しています★3。 また、アフリカ系アメリカ人の大移動Great Migration★4の後には、特定の都市や住宅コミュニティを隔離する人種差別的政策であるレッドライニング★5の歴史もあります。重要なのは、これらが住宅所有や多世代にわたる人種間の貧富の格差に影響を与えただけでなく、食料へのアクセスや、裏庭yardを所有すること、そしてもちろん、家庭菜園home gardenをすることにも影響を及ぼしたということです。政策に関していえば、小規模農園がどのように営まれるかに影響を与える農業政策もあります。米国では大豆やトウモロコシなどの商品作物への補助金が最も大きく、これが意味するのは、大規模農園のほとんどは、人間が食べることのない[むしろ家畜の餌となる]作物を生産しているということです。このような政府の政策に直面しても、都市農園のようなコミュニティ主導の空間は、人々を、食料源や、農作業から生まれる失われた社会形態に再び結びつけることができます。しかし「できる」ということは、実際にそう「する」ということを意味しないことに注意することは重要です——これが『ケールを越えて』の鍵となるメッセージのひとつです。不平等を生み出す社会の構造的な力学に注意を払わなければ、農園や庭園は、意図せずして不平等を強化することがありえます。例えば、庭園がジェントリフィケーションにつながり、長年住んでいた比較的低所得の住民を外に追いやってしまう場合などです。

トゥーリーレイク強制収容所の日系アメリカ人農民たち

From Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project via The National Archives.

ムレーン──これらの都市農園は、ある意味で政府の欠陥に対抗して作られたものであるにもかかわらず、自己決定という妙に「アメリカ的」なイデオロギーを表象してもいることが面白いと感じます。

レイノルズ──そうですね、ある意味では。しかし、都市農園を自己決定というポジティブな実践として説明することは、危険でもありうると私は思います。私たちの仕事では、都市農園が必ずしもラディカルな自己決定の実践であるとは考えていません。そう考えることはあまりにも決定論的です。自己決定と、政府が国民に基本的生活必需品を提供することから手を引くことを可能にする新自由主義のメカニズムの間は、紙一重です。言い換えれば、都市農園を「自己決定」の解放的実践として扱うことは、権限を移譲する現在の政府の政策がうまく機能している証拠として、政府によって簡単に横取りされてしまうのです。さらに、コミュニティに根ざした農園の自発的取り組みのすべてを「自己決定」の実践と呼ぶことは、農園が実際には所有を奪う場であり続けているという事例を曖昧にしかねません。例えば米国での日本人の経験を考えてみると、1940年代にアメリカ政府が日系人と在米日本人を敵国人収容所に送るまで、多くの日本人や日系アメリカ人が西海岸で何十年にもわたってさまざまな形態の農業に従事していたのです。米国の農業空間には、そのような歴史があることも忘れてはなりません。

ムレーン──私はこの都市農業の両義性を興味深く感じます。私が都市農園について考え始めた理由のひとつは、建築の完成予想図のなかで都市農園に出会うことが非常に多かったからです。これらの図のなかでは、小さな農園はコミュニティの食料生産を可能にする空間というよりも、むしろ建築家の政治的進歩主義を伝えるための象徴として描かれているのです。私はいつもこれを皮肉なことだと考えてきました。というのは、このような完成予想図を含むプロジェクトの多くが、農園によって助けられるだろうと意図されていた、まさにその人たちの居場所を奪うことになるものだったからです。都市農園に対するこのようなトップダウン的アプローチについてはどう思われますか?

レイノルズ──この問題の良い解決策は、つねにユーザー中心のデザインを重視することだと思います。もし農園をデザインするのであれば、コミュニティのなかで時間を過ごし、農園が望まれているものなのかどうかを尋ねることが重要です。都市農業に関心のあるデザイナーは、自分たちの目標は何なのかと自身に問う必要があります。コミュニティを助けることなのか、それとも庭園を作ることなのか。この2つは必ずしも一致しないこともあります。農園が社会の改善を自動的に約束するわけではありません。庭園がジェントリフィケーションにつながる場合のように、そのコミュニティに有害な影響を与える可能性さえあるのです。

ムレーン──都市農園のネガティブな効果として考えられることには何がありますか?

レイノルズ──少なくとも2つの問題が考えられると思います。ひとつは、先にも述べたように、ジェントリフィケーションです(都市農園は、不動産の価格設定によって、実際には不平等を増大させるようなかたちで作られることがあります)。もうひとつの問題は「グリーンウォッシング」です。環境保護主義者のレトリックを使いながら、意図的であるにせよないにせよ、より深いシステムの問題をカモフラージュしてしまうことです。これは、ネヴィン・コーエンと私が私たちの本で論じたことです。都市農園は時として、そもそも農園をその可能な解決策とさせたより深い問題から、公衆や政府の注意を逸らしてしまうことがあるのです。

ムレーン──都市農園はローカルな諸問題から生まれたときに最もよく機能するとおっしゃいましたが、都市農園の利点はこうした特定の文脈を超えて適用できるものなのでしょうか。米国の人たちは、そこでの学びをどのようにスケールアップしているのでしょうか。また、その学びを国際的に交換することは可能でしょうか。例えば福島では、土壌の汚染と政府の対応が、すでに存在していた不平等をより明瞭にしました。汚染された地域で食料を生産していた人々はもはやその生産物を売ることができなくなり、東北地方と東京など他の場所との間の社会的・経済的格差を悪化させたのです。人類学者のリョウ・モリモトは、農地の除染を目的とした政府の戦略が、経済的・生態的な格差をさらに生み出し、すべての生き物の「相互結合性」(縁)という実在を断ち切ってしまったことを明らかにしています★6。

レイノルズ──この問いについてはよく考えます。もし都市農園の目標が社会正義、人種的平等、経済的平等、食の平等などであれば、これらはたしかにどんな規模にもスケールアップするに値する目標です。あなたが説明された福島の経験を、規制されていない汚染の侵食にたえず対処し続けなければならない米国における都市農園のような、他の国々の汚染の例と結びつけることができます。ここでも、都市農業を食料生産を超えた平等という目標を達成するためのツールと考えるなら、これらの課題はローカルな文脈を超えて翻訳可能な、共同的なものとなります。

ムレーン──都市農業のスケールアップに関していえば、現在、農業技術(いわゆる「アグテック」)に対する投資が大幅に増えています。都市農園は、地域住民のために小規模に運営されるのが一般的です。しかしこのモデルは、大都市からの投資を利用して田舎にまるで都市のような空間規模の農園を建設する大企業によってひっくり返されつつあります。従来の都市農園のモデルでは、いわばアメリカの農村が都市にもたらされていましたが、現在では都市が農村部に入り込んでいっているのです。例えば、ケンタッキー州の「AppHarvest」のような大規模プロジェクトは、雇用喪失と経済的不平等で打撃をひどく受けた地域にシリコンバレーからの投資を呼び寄せています★7。このような農業の新しい変化についてどう思われますか。「アグテック」は課題解決型の都市農業の支援に活用されるのか、それともこの新しい資金のパイプラインは不平等を深めることになるのか、お考えをお聞かせください。

AppHarvestの施設、ケンタッキー州モアヘッド

Source: https://www.appharvest.com/press_release/appharvest-opens-one-of-the-worlds-largest-high-tech-greenhouses-in-appalachia-to-redefine-american-agriculture/

レイノルズ──新しい農業技術は、たしかに社会正義や不平等の問題を支援するような仕方で利用できると思いますが、懸念もあります。アグテックの支援を受けてこれらの農園がスケールアップする場合、地域コミュニティの懸念が見捨てられる可能性があるのです。例えば、あなたが鉄道コンテナで野菜を栽培している場合、地域コミュニティとのつながりは明白ですが、規模が大きくなると、こうしたつながりを維持することが難しくなります。アグテックの力を借りてスケールアップするには、コミュニティ密着型の営みから政治的・経済的資源が吸い上げられないように、地元の食材を強力に支援する政策とセットである必要があります。雇用を欠いている場所にアグテック企業がやってくると、資源をめぐるローカルな競争を生み出します。もしこれらの企業が、彼らが約束する進歩にはそれだけの価値があるということを地元の行政に説得できなければ、ローカルな農園の自発的営みが損害を受けることになります。これについては他所で論じたことがあり、私の研究プログラムの継続的な一部になっています★8。

注

★1──ケールのような野菜は、裕福な白人が摂る健康食の象徴でもある。本書の狙いは非白人が営む都市農園の紹介にあり、本書のタイトルは「想像を絶するもの」を意味する言い回しである“Beyond the Pale”をもじったものだ(「青白いpale」は白人も示唆する)。

★2──Kristin Reynolds and Nevin Cohen, Beyond the Kale: Urban Agriculture and Social Justice Activism in New York City (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2016) 参照。

★3──Monica M. White, Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2021) 参照。

★4──米国南部での差別から避難し、北部でのよりよい生活を求めて行われた20世紀前半における黒人の大移動のこと。

★5──金融リスクが高いと考えられた黒人居住区を融資対象から除外する目的で、その地区を確定するために行われた赤線引き。

★6──Ryo Morimoto, “A Wild Boar Chase: Ecology of Harm and Half-Life Politics in Fukushima,” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 37, no. 1 (2022), 69-98 参照。

★7── https://www.appharvest.com/2.0/参照。

★8──Kristin Reynolds and Ségolène Darly, “Commercial Urban Agriculture in the Global City: Perspectives from New York City and Métropole du Grand Paris,: CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute (2018), https://www.cunyurbanfoodpolicy.org/news/2018/12/11/lscislvsr7spj7834v9ls796n6xm7h 参照。

■訳:松田法子+平倉圭/Translation by Noriko Mutsuda + Kei Hirakura

[ニューヨーク:2022年3月22日17:30〜/東京:3月22日6:30〜、Zoomにて]

When is a farm a garden? In the English language, “farm” and “garden” are often kept distinct. A farm is understood as a place where food is produced while a garden is a human-made space with philosophical potential; it is a microcosm that embodies a given culture’s values and civilizational outlook. For this reason, art and architecture historians more commonly study Japanese, French, and British gardens, not these countries’ respective farms. However, farms can also represent a culture in a way that a garden traditionally does. Nowhere is this more evident than in the urban farms of the United States. The urban farm is in many ways a microcosm of contemporary American life, framed by issues of racism, economic inequality, social justice, healthcare access, divergent definitions of governmental responsibility, and the always looming influence of the country’s high-tech industries.

In urban Japan, small pieces of farmland are a surprisingly common sight. Someone arriving in Tokyo for the first time expecting an unending concrete sprawl might be surprised to see a rice paddy next to an apartment building. I once lived in Nerima-ku near a patch of farms and a farmer-maintained “vending machine” where I could purchase daikon or cabbage for a few hundred yen. Such close proximity between living and farming in Japan is a result of the government’s embrace of mixed-use zoning, a system that allows residential, agricultural, commercial, and industrial sites to co-exist in varying patterns. In the United States however, most cities have been deeply shaped by exclusionary single-use zoning. Though often described as a means of keeping residential spaces free of the nuisances of commerce and industry, single-use zoning has long been used as a tool to separate rich from poor and white people from peoples of color. The absence of agricultural space near or within cities is not just depleting cities of food and greenery, it is a spatial artifact of the country’s past and present efforts to racially and economically divide its population.

Nerima-ku vending machine, photo by André Viljoen and Katrin Bohn, 2018.

Los Angeles zoning map showing the split between single-family zoning and commercial zoning

In light of this history, urban farming in the United States is undoubtedly politically charged. The ability to produce one’s own food has not always been guaranteed; indigenous and minority populations have been forcibly removed from land, denied access to land through exclusionary loan programs, and have had their epistemologies of knowing the land erased. Perhaps more than food production then, urban agriculture is a means of engaging with this history and forging new communities from it. Today, the many different histories of agricultural exclusion in the United States have given rise to just as many experiments of inclusion. These include small-scale farms on private property and backyards, community farms engaged in both food production and student outreach (Red Hook Farms, NYC), attempts to reinvigorate Indigenous modes of agriculture (San Xavier Co-Op Farm, Arizona), networks that help assist burgeoning urban farms (Black Farmer Fund, New York), and city-wide incentive programs (Los Angeles County Urban Agriculture Incentive Zone Program).

So, what do these sorts of farms and programs have to do with the Habitat Building History and our search for ways towards “Mode 4”? Looking at the HBH diagram and its curving arrows of progression, I have often thought about Mode 4 as a way to move forward by looking backward. In the urban farm, this act of looking backward is practiced by learning about and reacting to the country’s violent past and understanding ways of knowing nature that have been erased. However, this is not to say that these farms are nostalgic. Instead, they are reviving something that has been lost amidst the destructive machinations of capitalist industrialization, nurturing it, and hoping it will grow in the future. Recent work being done by Indigenous thinkers in the United States exemplifies this approach. A-dae Romero-Briones, Director of Programs for the First Nations Development Institute, has called for a “regenerative” agriculture based in “decolonizing” our understanding nature. She argues that “at the heart of the concept regeneration is wanting to renew and correct some of the missteps that have taken us to the point of environmental damage and degradation.”

A-dae Romero-Briones, “Indigenous and Mainstream Food Systems Compared.” From A-dae Romero-Briones, “Fighting for the taste buds of our children,” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, volume 9, supplement 2 (2019), 37.

In order to learn more about urban farms in the United States and their potential to “current these missteps,” I spoke with Prof. Kristin Reynolds, a scholar/activist working in New York City. In 2016, Reynolds co-authored Beyond the Kale: Urban Agriculture and Social Justice in New York City with Nevin Cohen, a book concerned with understanding the ways that urban faming can be a vehicle for hyper-local platforms of community-making and social change. Prof. Reynolds and I spoke about the methods of studying urban agriculture, the political ambiguity of urban farms, and the future of urban agriculture in the wake of new technology.

■Interview

Kristin Reynolds

MM: Prof. Reynolds, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me. I was curious if you could first give me some background information on what led you to work in the field of urban agriculture. KR: I started getting interested in urban agriculture for social justice reasons, really, and starting in California connecting my graduate research at the University of California, Davis and the UC Small Farm Program, which served small-scale, and limited resource farmers. I then moved to The New School in New York and was involved with various projects, including a project called Five Borough Farm, which eventually led to my book Beyond the Kale, coauthored with my colleague Nevin Cohen. I've always been committed to and interested in the urban agriculture communities where I live.★1 As community farming was blossoming in the early 2000s, I came to understand that there was an underserved portion of agriculture: farming in cities. This observation coincided with the emergence of the food justice movement in the United States.

Cover of Kristin Reynolds and Nevin Cohen, Beyond the Kale: Urban Agriculture and Social Justice Activism in New York City (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2016).

I think my dual experience as a volunteer and researcher is important in this context. I feel an ethical responsibility to be in community with urban farmers, so that I’m not just parachuting in to collect information and leave. In my research, I wanted to work against a growing stereotype that urban farming is an activity led by white people, because that is simply not true. Through my work in New York City, I came to know many women and people of color who successfully operate urban farms, and some of these leaders are the focus of Beyond the Kale. They are using urban agriculture in ways that surpass producing food; they use their farms and gardens to articulate and address very specific social justice questions in their community environments.

Rob Stephenson, United Community Centers Farm, Brooklyn, NYC, 2011.

Rob Stephenson, Culinary Kids Garden, Queens, NYC, 2011.

Rob Stephenson, Hell’s Kitchen Rooftop Farm, Manhattan, NYC, 2011.

MM: Given that our readership extends to Japan where issues of food inequality are much different, I was curious if you could give a brief synopsis of food inequality in the United States. What sort of social justice issues were being responded to in the urban farms you studied?

KR: The answer is of course complex. As prominent environmental justice scholar Dr. Monica White has demonstrated in her work (notably her book Freedom Farmers), historically, enslavement, and post-enslavement realities have deeply impacted views that some African-American people have towards agriculture.★2 In the wake of the Great Migration, there is also the history of redlining, a racist policy of segregating cities and residential communities. Significantly, this affected home ownership and multi-generational, racialized wealth disparities, but has also affected food access and the ability to own a yard, and of course, have a home garden. Speaking of policies, there are also agricultural policies that influence how small-scale farms operate. The United States most significantly subsidizes commodity crops like soy and field corn, meaning that most large-scale farms produce material that is never eaten by humans [but rather fed to livestock]. In the face of such governmental policies, community-led spaces like urban farms can re-connect people to their food sources and the lost forms of socialization that emerge from agricultural work, though it is important to note that just because they can do this, does not mean that they do – this is one of the key messages in Beyond the Kale. Without attention to the structural dynamics in society that create inequities, farms and gardens can unintentionally reinforce inequality, such as when gardens lead to gentrification and push out long-time, relatively low-income residents.

Japanese-American Farmers at Tule Lake Concentration Camp, from Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project via The National Archives.

MM: I find it interesting that even though these urban farms are in a sense made in opposition to governmental deficiencies, they also represent a curiously “American” ideology of self-determination.

KR: Yes, in a sense. But I think that describing urban farms as a positive practice of self-determination can be dangerous as well. In our work, we never approach an urban farm as necessarily a practice of radical self-determination, that would be too deterministic. There's a fine line between self-determination and the mechanisms of neoliberalism that allow the government to step back from providing fundamental necessities to its people. In other words, treating the urban farm as a liberatory practice of “self-determination” can easily be co-opted by government as evidence that current policies of government devolution are working. Furthermore, calling all community-based farming initiatives practices of “self-determination” can obscure instances where farms have actually been sites of dispossession. Thinking of the Japanese experience in the United States for example, many Japanese and Japanese-Americans worked in various forms of agriculture for decades on the West coast before the US government sent Japanese-Americans and Japanese residents in the US to internment camps in the 1940s. We have to remember that agricultural spaces in the United States contain such histories as well.

MM: I find this ambiguity of urban agriculture interesting. One of the reasons I started to think about the urban farm was because I so often encountered them in architectural renderings. In these images, the small farm is not so much a potential space for food production of community, but rather a symbol meant to communicate the architect’s political progressivism. I always found this ironic given that many of the projects that included these renderings would most likely displace the very people that the garden was meant to help. What do you think about this kind of top-down approach to urban farming?

KR: I think a good solution to this problem is to always focus on user centered design. If you're going to design a garden, then it is important to spend time in the community and ask if the community if a garden is what is desired. Designers interested in urban agriculture should ask themselves what their goal is. Is it to help a community or is it to build a garden? Sometimes those two things don’t necessarily go together. Gardens don’t automatically promise social betterment; they may even end up having a deleterious effect on that community, such as in cases where gardens lead to gentrification.

MM: What are some possible negative effects of an urban garden?

KR: I think there are at least two possible problems. The first, as I mentioned previously, is gentrification. [Urban gardens can be implemented in a way that actually increases inequality due to real estate pricing.] The second problem is “greenwashing,” the use of environmentalist rhetoric while, whether intentionally or unintentionally, camouflaging deeper systemic problems. This is something that Nevin Cohen and I argued in our book, that the urban garden can sometimes divert public and governmental attention from the deeper problems that made the garden a possible solution in the first place.

MM: As you’ve mentioned, urban gardens work best when they emerge from local problems, so I was curious whether the benefits of an urban garden can be applied beyond these specific contexts. How do people in the United States scale up the lessons, and can these lessons be exchanged internationally? Thinking of Fukushima for example, the contamination of soil and the government’s response made already existing inequalities more evident. People who produced food in the region could no longer sell their goods, exacerbating a social and economic divide between the Tōhoku region and places like Tokyo. The anthropologist Ryo Morimoto for example has shown how governmental strategies to decontaminate farmland have only further created economic and ecological divides, severing the reality of the “interconnectedness” (en) of all living things.★3

KR: I think about this question lot. If the goal of an urban garden is social justice, racial equality, economic equity, food equity, etc., then these are certainly goals that deserve to be scaled up to any size. We could connect the Fukushima experience you’ve described to international examples of contamination, like in the United States where urban farms have to constantly deal with the encroachment of unregulated contamination. Again, if we're looking at urban agriculture as a tool to achieve goals of equality that go beyond food production, then these challenges are collective ones that are translatable beyond local contexts.

MM: Speaking of the scaling up of urban agriculture, we are currently seeing a massive increase of investment in agricultural technology (so-called “ag tech”). Urban farms typically operate at a small scale, serving local populations. However, this model is being inverted by large companies who use investment capital coming from major cities to construct city-size farms in rural locations. In the older model of the urban farm, rural America was brought into the city, but now we are seeing the city come into rural areas. For example, large projects like “AppHarvest” in Kentucky are drawing investment from Silicon Valley into areas hit hard by job loss and economic inequality. ★4 I’m curious what you think about this new mutation of agriculture. Do you see “ag tech” being utilized to support issue-based urban agriculture, or is this new pipeline of money deepening inequality?

AppHarvest facilities, Morehead, Kentucky.

Source: https://www.appharvest.com/press_release/appharvest-opens-one-of-the-worlds-largest-high-tech-greenhouses-in-appalachia-to-redefine-american-agriculture/

KR: I think that new agricultural technology can certainly be used in a way that supports social justice and issues of inequality, but I do have concerns. When these farms scale up with the support of ag tech, there is a possibility that the concerns of the local community are superseded. If you are growing greens in a railroad container for example, the connection to the local community is obvious, but at a larger scale, these connections become harder to maintain. Scaling up with the help of ag tech should also be paired with strong policy support of local food so that political and economic resources are not siphoned from community-based operations. The arrival of ag-tech firms in places hurting for jobs creates local competition for resources, and if these companies con convince local governments that the progress they promise is worth it, then local farming initiatives will suffer. I have written about this elsewhere and it is an ongoing part of my research program. ★5

Note:

★1──See Kristin Reynolds and Nevin Cohen, Beyond the Kale: Urban Agriculture and Social Justice Activism in New York City (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2016).

★2──See Monica M. White, Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

★3──See Ryo Morimoto, “A Wild Boar Chase: Ecology of Harm and Half-Life Politics in Fukushima,” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 37, no. 1 (2022), 69-98.

★4──See https://www.appharvest.com/2.0/.

★5──See Kristin Reynolds and Ségolène Darly, “Commercial Urban Agriculture in the Global City: Perspectives from New York City and Métropole du Grand Paris,: CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute (2018), https://www.cunyurbanfoodpolicy.org/news/2018/12/11/lscislvsr7spj7834v9ls796n6xm7h.

[New York City:5:30 PM, March 22, 2022/Tokyo:6:30 AM, March 22, on Zoom]

- 庭以前──旧石器人たちの暮らしと空間利用

-

Before the Garden: The life and the space utilization of Paleolithic people

/在庭院以前——旧石器时代人类的起居与空间利用

藤田祐樹/Masaki Fujita - 極小の庭──盆栽

-

Bonsai as Minuscule Garden

/极小之庭——盆栽

依田徹/Toru Yoda - アヴァン・エディブル・ガーデニング──クリスティン・レイノルズと話す、米国における都市農園の政治

-

Avant Edible Gardening: Speaking with Kristin Reynolds on the Politics of Urban Farmingin the United States

/可食用的先锋园艺──对话克里斯汀・雷诺兹,美国都市中的农场政治

マシュー・ムレーン/Matthew Mullane - 人でなしの庭──更新世再野生化の試み

-

The Garden of the Inhuman: An Attempt at Pleistocene Rewilding

/非人之庭——在更新世尝试进行再野生化

松田法子/Noriko Matsuda - 座談:構築様式のモデルとしての庭

-

The Roundtable Discussion

/座谈:庭院作为构筑样式的模型

平倉圭+青井哲人+日埜直彦+松田法子+Matthew Mullane+藤井一至+藤原辰史/Kei Hirakura+Akihito Aoi+Naohiko Hino+Noriko Matsuda+Matthew Mullane+Kazumichi Fuji+Tstsushi Fujihara

協賛/SUPPORT サントリー文化財団(2020年度)、一般財団法人窓研究所 WINDOW RESEARCH INSTITUTE(2019〜2021年度)、公益財団法人ユニオン造形財団(2022年度〜)