第1号 特集:SF生環境構築史大全 A Sci-Fi Guide to Habitat Building History 科幻生環境構築史大全

生環境構築史とSF史:基調講演

巽孝之【慶應義塾大学文学部教授、アメリカ文学】

Habitat Building History and History of Sci-fi: Keynote SpeechTakayuki Tatsumi【Professor of American Literature, Keio University】

生環境構築史与科幻小说:主旨演讲

¥The history of science fiction begins in fairly straightforward fashion. The forerunner of the genre was Frankenstein (1818), by the British novelist Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, which served as inspiration for the American writer Edgar Allan Poe, France’s Jules Verne, and England’s H.G. Wells. In the early 20th century, Hugo Gernsback, an American engineer who had emigrated from Luxembourg, launched Amazing Stories, the first SF magazine, and established SF as a genre. Since 1953 the annual Hugo Award, which honors him as the “father of science fiction,” has been considered the ultimate quality-assurance label for contemporary SF works. Of course, if Gernsback was SF’s father, then Shelley, Poe, Verne and Wells must be considered its grandparents.

But how should we summarize the history of SF since then?

[2020.11.1 UPDATE]

1. SF史の三段階──外宇宙、内宇宙、電脳空間

SF史を概観するのは、そう難しくない。19世紀前半、イギリス作家メアリ・シェリーの長編小説『フランケンシュタイン』(1818)を嚆矢として、その精神をアメリカ作家エドガー・アラン・ポーやフランス作家ジュール・ヴェルヌ、イギリス作家H・G・ウェルズが継承した。そして20世紀前半、ルクセンブルク系アメリカ移民の技術者ヒューゴー・ガーンズバックが世界初のSF専門誌『アメージング・ストーリーズ』を創刊しジャンルSFの起源を成す。その結果、この「SFの父」の名を記念し年間最優秀SF賞「ヒューゴー賞」が、現代SF最高の品質保証ラベルとして1953年以来継続している。もちろんガーンズバックが父ならばシェリーやポー、ヴェルヌ、ウェルズはSFの祖父母である。

では、以後のSF史はどのように語ることができるか。

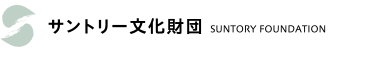

極々単純にまとめるなら、まず第一段階、1920年代からSF黄金時代と呼ばれる50年代までは、いわゆる「外宇宙」(outer space)を目指す作品が支配的だった。SF黄金時代の立役者が『ファウンデーション』シリーズのアイザック・アシモフ、『2001年宇宙の旅』シリーズのアーサー・C・クラーク、『宇宙の戦士』のロバート・A・ハインラインの御三家だったといえばイメージが掴みやすいだろう。当時はSFはあくまで「空想科学小説」(science fiction)転じては「未来予測小説」であり、名編集者ジョン・W・キャンベルが唱道したように、現在のデータを元にそれを未来へむけて「外挿すること」(extrapolation)に、いささかの疑問も挟まれなかったのである。

左から『ファウンデーション』(May be found at the following website: http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?14435., Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9908274)

『2001年宇宙の旅』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14566711)

『宇宙の戦士』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6261365)

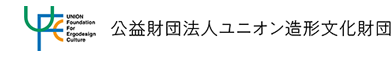

これが第二段階、すなわち1960年代に入ると、イギリスで革命が起こる。J・G・バラードを筆頭にブライアン・オールディス、マイケル・ムアコックが引き起こした「ニューウェーヴ運動」が、それだ。当時は、ケネディ大統領が提唱したニュー・フロンティア計画に基づき、米ソの宇宙開発競争がデッドヒートを繰り広げていた。しかし基本的に反アメリカニズムを掲げるバラードらは、今必要なのは外宇宙ではなく内宇宙(inner space)、すなわち無意識世界の探求だと断言する。彼自身の『結晶世界』(1966)をはじめとする破滅四部作に見られるように、そこで導入されるのは精神分析理論であり、ダダ=シュールレアリスム詩学であり、対抗文化思想であり、さらにはマーシャル・マクルーハンらメディア哲学者が一丸となって夢見た「グローバル・ヴィレッジ」の理想であった。バラードはやがて「テクノロジー空間が新たな自然と化した」ことを認識して「技術論的風景」(technological landscape)の方へ重点移動していく。

ここで肝心なのは、彼らニューウェーヴ作家たちがSFを「空想科学小説」(science fiction)ならぬ「思弁小説」(speculative fiction)と読み替え、その方向性において、アメリカでも『ブレードランナー』原作者フィリップ・K・ディックやトマス・ディッシュ、サミュエル・ディレイニーら「3D」と称される作家たちが高い評価を受けるに至ったことだ。加えて、外宇宙を希求するようでいて、その実、内宇宙への指向を強く打ち出したポーランド作家スタニスワフ・レムとその代表作『ソラリス』(1961)『砂漠の惑星』(1964)も忘れるわけにはいかない。レムの描く外宇宙の知性体はいずれも神人同型論から逸脱していたためにロシア語版では検閲されたものの、異星を描きつつ地球人自身の内宇宙を掘り下げていく展開は紛れもなく思弁小説であり、彼がカフカやボルヘス、ナボコフとも比肩する存在と評価される所以である。米ソ冷戦時代にレムが描き出した二重太陽が巡る惑星ソラリスというコンセプトは、のちにクラークの『2010年宇宙の旅』(1982)や小松左京の『さよならジュピター』(1983)における木星太陽化計画に身近なものとなり、そこには宇宙論的ユートピアの可能性も夢見られているが、現代ではそれをさらに一捻りし、三重太陽が巡り苦難に喘ぐ惑星のディストピアを設定したのが劉慈欣の『三体』(2008)であることも言及しておく。

左から『結晶世界』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10421553)

『Androidは電気羊の夢を見るか?』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21070569)

『ソラリス』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20699697)

『三体』(合理使用, https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=748867)

1960年代のニューウェーヴ運動は、一見したところ、モダニズム運動の再来のように映るかもしれない。しかし、ニューウェーヴ運動は少なからぬ女性作家たちを巻き込んだ。イギリスではパミラ・ゾリーン、アメリカではアーシュラ・K・ル=グィンといったフェミニスト作家たちが、そしてカナダでは作家のみならずニューウェーヴの理論的イデオローグ兼アンソロジストとしても健筆を振るうジュディス・メリルが、思弁小説としてのSFを強く支持したのだ。ここで、ル=グィンのヒューゴー賞受賞作『闇の左手』(1969)が両性具有を扱い、ジェイムズ・ティプトリー・ジュニアが性別を偽り、前掲ディッシュやディレイニーがゲイ作家でもあったことを勘案すれば、「内宇宙」の中でも70年代に特権化されたのは「性差宇宙」(gender space)であったのが判明しよう。

やがて1970年代より開発の進むインターネットを踏まえ、いわゆるパーソナル・コンピュータが流通し始めた頃、1984年にサウス・キャロライナ州出身のカナダ作家ウィリアム・ギブスンが自身の命名になる「電脳空間」(cyberspace)を舞台に据えた第一長編小説『ニューロマンサー』が、サイバーパンク運動を引き起こす。ギブスンの盟友ブルース・スターリングがスポークスマンとなり、ジョン・シャーリー、ルイス・シャイナー、パット・キャディガン、ルーディ・ラッカーらが共作やアンソロジー参加などで繰り広げた活動は、内宇宙でも外宇宙でもない電脳空間が新たなフロンティアたりうることを示し、イギリスにおいても1980年代後半以降にはリチャード・コールダーやイアン・マクドナルド、日本においても1990年代には柾悟郎、2000年代には伊藤計劃といったポスト・サイバーパンク作家を輩出した。21世紀SFを牽引するオーストラリアのハードSF作家グレッグ・イーガンや中国系アメリカ作家テッド・チャンも、この系統を踏まえているだろう。

左から『闇の左手』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20131698)

『ニューロマンサー』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2529044)

もっとも、サイバーパンク的なるものの等価物はすでに日本SF第三世代の神林長平や大原まり子が同時代1980年代前半において生み出しており、国際的には大友克洋の漫画『AKIRA』(1982〜90)や士郎正宗原作、押井守監督のアニメ『攻殻機動隊』(1995)が浸透したことを考えると、こうした世界的同時多発のうちに、21世紀におけるクール・ジャパンの源流を求めることができるかもしれない。その影響を受け、地球温暖化以後、人新世以後の環境批評的視点からいわゆるバイオパンクを促進しているヒューゴー賞受賞作家パオロ・バチガルピの『ねじまき少女』(2009)は水没した近未来のタイを舞台に蒸気でも電気でも原子力でもなくゼンマイを機軸に発展した生環境構築の可能性を描いて衝撃を与えた。

2. フロンティアの消息──テラ・インコグニタからテラフォーミングへ

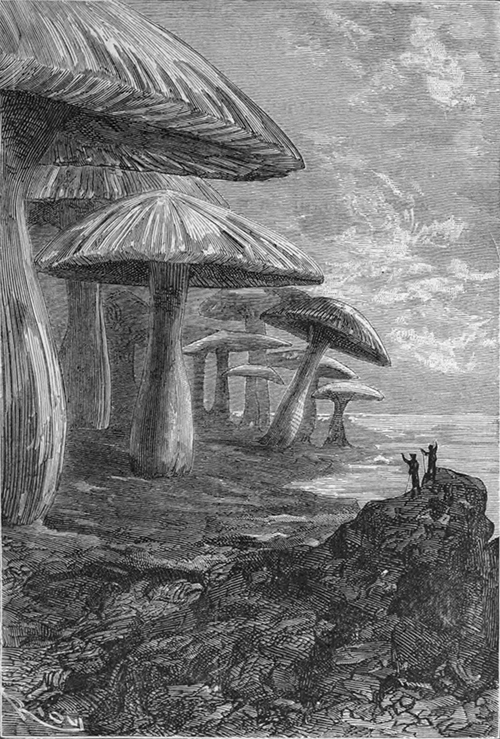

さて、以上のようにまとめてくると、一種のフロンティア・スピリットがSF史における多様な「未踏の世界」(terra incognita)を開発し、それが現実の文明にもフィードバックしていった構図が見えてくるだろう。げんに、シェリーの『フランケンシュタイン』において人造人間が姿を消すのは、当時まだ未踏の世界であった北極であり、ポーの『アーサー・ゴードン・ピムの冒険』(1837)の最終場面で描かれるのも、まだ探検が進んでいない南極であった。特に後者が南極の一点から地球の内部へ潜り込むという地球空洞説を前提に書かれていたことは、フランスのジュール・ヴェルヌの『地底旅行』(1864)や『氷のスフィンクス』(1897)に影響を与えた点で重要である。ポーはこの着想を、先輩作家のジョン・クリーヴズ・シムズがキャプテン・アダム・シーボーン名義で発表した空洞地球小説『シムゾニア』(1820)から得た。同書は空洞地球内部にシムゾニアという白人の平和な王国が存在し、そこでは戦争も病気も一切なく、かつて悪に染まった種族がいたもののその連中は追放されて地上に蔓延っていることを克明に記述している。こうしたユートピア的発想が、アメリカ南部の白人貴族社会を重んじたポーを啓発したのは、推測に難くない。そう、本書『シムゾニア』は、まさに空洞地球の人々がその暮らしぶりそのものによって地上の文明社会を批判するという生環境構築を浮き彫りにするのだ。

エドゥアール・リウーによる『地底旅行』の挿絵(Par Édouard Riou — http://jv.gilead.org.il/rpaul/Voyage%20au%20centre%20de%20la%20terre/, Domaine public, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11234108)

以後のアメリカは特に南北戦争を挟んで「明白なる運命」のもとに西漸運動を進め、1890年にはついに北米の地上からフロンティアが消滅した。けれど地上のフロンティアが消滅しても、フロンティア・スピリットは死なない。

1883年に来日し朝鮮にも滞在したボストン上流知識階級(ブラーミン)のパーシヴァル・ローエルは、のちにその著書『極東の魂』(1888)によってラフカディオ・ハーンすなわち小泉八雲に影響を与えた日本学者だが、彼は実は、日本の次に、火星の「運河」に夢中になり著書『火星』(1895)を発表、それがSFの祖父の一人H・G・ウェルズの名作『宇宙戦争』(1898)へ影を落とす。ローエルは日本でしばらく暮らすことで極東の人々の独特な個性を観察したけれども、他方、火星に存在が想定されていた運河が、そこには知的生命体が「暮らしている」という生環境的証拠であると確信したのだ。

大きさだけとれば、火星は地球のほぼ半分。ところが、火星の全表面積は、地球における陸地の全表面積とほぼ等しい。しかも、火星の自転周期は24時間37分、つまり地球の一日である24時間とほとんど同じ。ただし火星の公転周期は1・88年で地球の二倍近いため、それぞれの季節は地球における春夏秋冬のほぼ二倍の長さになる。つまり、地球人が移住するなら火星ほど適した場所はなく、火星人が何らかの事情で母星を捨てねばならなくなれば地球ほどに理想的かつ植民可能な生環境はないのである。

かくして、エイリアンといえば地球の侵略者だというステレオタイプが生まれ、ウェルズが火星人をデザインしたあとは、宇宙人といったらタコやイカ、エビやカニといったシーフード系に決まっているという固定観念ができあがった。世紀転換期は日清戦争から日露戦争にかけての時代ゆえに、欧米は日本の文化への憧れをジャポニズムという形で示しつつ、全く同時に黄色人種すなわちアジア系の進出を恐れる気持ちがイエローペリル(黄禍論的言説)をも蔓延させたので、他者に対する憧憬と恐怖がないまぜになったエキゾティシズムが同時代を支配していたのは疑えない。もっとも1965年から1973年にかけてアメリカの火星探査機マリナーが、1976年にはヴァイキング計画におけるランダー1号、2号が、火星には運河どころか海も生命も存在しない可能性が高いことを明らかにしている。

だが、一度火星に夢を見てしまったSF的想像力はとどまることなく、最新の知識をフル活用して、火星を地球とそっくりな環境に改造して暮らそうとする人々を描く作品は増える一方だ。こうした惑星地球化計画のことを、アメリカ作家ジャック・ウィリアムスンが1942年にテラフォーミング(terraforming)と名付けて以降、現代SFの巨匠クラークやハインラインはもとより、グレッグ・ベアやテリ・ビッスン、ロバート・フォワード、イアン・マクドナルドといった英米作家が、ぞくぞくとテラフォーミングSFを発表している。その極致が、アメリカ作家キム・スタンリー・ロビンスンが完成した火星SFの最高傑作『レッド・マーズ』(1993)、『グリーン・マーズ』(1994)、『ブルー・マーズ』(1996)の三部作である。

『Mars』シリーズ(By Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61259523)

3. モノリスは予言する──SF史縮図としての『2001年宇宙の旅』

以上、ジャンルSFの第一段階である「外宇宙」指向が世紀転換期における火星ブームと東洋へのエキゾティシズムがない混ぜになった形で発展したことが了解されたと思う。その第二段階である「内宇宙」指向からは高度成長期を批判するかのような終末論的光景がシュールレアリスム風に紡ぎ出され、相次ぐ核実験や地球温暖化に対する生態学的警鐘を鳴らした。そして第三段階である「電脳空間」は瞬く間に現代人の日常空間と化してしまい、アンチヒーローとして登場したコンピュータ・ハッカーは今やサイバー・テロリストの原型である。

こうしたSF史から見直すと第二段階の1968年、アポロ11号の月面初着陸に一年先立ち公開されたクラーク=キューブリック共作『2001年宇宙の旅』は過去・現在・未来のSF史を集約した作品として読み換えることができる。それはおそらく、生環境構築史とも何らかの形で連動するだろう。

エイリアンが四百万年前(小説では三百万年前)の地球に暮らす類人猿のもとへ送り込んだ謎の石板(モノリス)は、人類進化の触媒にして教育装置だった。しかしやがて21世紀、月面でそれと同様なモノリスが発見され異様なノイズを発するが、この第二のモノリスは人類進化の水準をエイリアンに知らせる通信装置だった。そしてスーパーコンピュータHAL9000を搭載した宇宙船ディスカバリー号は木星(小説では土星)へ向かう途上、HALの発狂により漂流し、ボーマン船長は木星付近で巨大なる第三のモノリス、つまり星々すらその内部で複製し再構築可能な超時空間「スター・ゲイト」に飲み込まれ超進化を遂げる。

三つのモノリスがSFの三段階に対応していることに注目してほしい。第一のモノリスは外宇宙の知的生命を進化させるベく送り込まれた植民地主義的な教育装置であり、第二のモノリスはマクルーハンの言う「グローバル・ヴィレッジ」を彷彿とさせる、人間の内宇宙すら相互接続可能なメディアとしての通信装置であり、そして第三のモノリスは文字通りその内部に世界を複製し人間の生体情報すら分解し再構築してしまえる電脳空間にほかならない。モノリスの三段階は、まさに現代SF史そのものではないか。

ここで肝心なのは、クラークがこのエイリアンをウェルズ的な帝国主義的侵略者ではなく「星々という畑の農夫」(farmers in the fields of stars)として性格造型したことだ。宇宙で芽生えた知的生命体の進化を促進すべく干渉するこのエイリアンは、自身は身体を捨て精神と思考を金属とプラスチックの中に移植し、知識を空間へ、思考を光の中へ蓄積する方法論を発見して、ついに純粋エネルギーと化した銀河系の支配者(lords of the galaxy)なのである。

その影響下、グレッグ・イーガンの『ディアスポラ』(1997)やウォシャウスキー兄弟監督の『マトリックス』三部作(1999〜2003)など、肉体なきソフトウェアとして電脳空間を生環境とする人類が夥しく描かれてきた。

しかし、クラークのようにエイリアンによる人類超進化計画を強硬な植民地支配政策ではなく一種の農業と捉える視点を最も着実に受け継いだ作品としては、クリストファー・ノーラン監督が2014年に制作した映画『インターステラー』にとどめをさす。あたかもノーベル文学賞作家ジョン・スタインベックの『怒りの葡萄』(1939)をなぞるかのように、農夫ジョセフ・クーパーは大規模な疫病のため農業的収穫が見込めなくなった地球を諦め、外宇宙に理想の惑星を求めるが、ブラックホールをへて帰還しようとした時には、エイリアンが作ったとしか思われない、どこかボルヘスのバベルの図書館を思わせる四次元構造体の中へ彷徨い込み、時間と空間を超える。しかし、モノリスを思わせるこの四次元構造体は、エイリアンというより未来人が制作したものであるらしい。そして救助されたクーパーは、地球に残してきた自身の娘が偉大な科学者となって、土星軌道上に構築したオニール型コロニーのユートピア的生環境「クーパー・ステーション」で目を覚まし、そこには地球に残してきた農家クーパー家も復元されていることを知る。

一見したところ単純明快な物語だが、にもかかわらず本作品『インターステラー』はSFが長く描いてきたエイリアンがハリウッド的類型の異星からの悪辣な侵略者ではなく、実は遠い将来、血肉すら克服した未来の人類、いわばポストヒューマンかもしれないこと、人類の外宇宙進出の夢すらも、宇宙の農夫たちによる生環境構築の結果かもしれないことを訴えた点で画期的である。それは伝統的なSF的外宇宙進出概念自体の批判であるとともに、生環境構築4をも導く洞察として、しかも半世紀以上前にクラーク=キューブリックが提起した問題意識を批判的に発展させたヴィジョンとして、多くの示唆を投げかける。

左から『ディアスポラ』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41668112)

『マトリックス』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3664863)

『インターステラー』(Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42681446)

4. 結語──郝景芳『折りたたみ北京』

最後に、中国の高名な女性SF作家・郝景芳の傑作『折りたたみ北京』(2016)に言及して締めくくりたい。というのも、このヒューゴー賞受賞作は、一つの都市の人民が階級に基づく地域別に都市空間をタイムシェアリングし、一定の時間が来たら文字通り一定の階級が地下から地上へ、そしてそれまで地上を占めていた一定の階級が今度は地下へと回転するダイナミックな力学を描いている点で、今日最も生環境のヴィジョンに密接に関わると確信するからである。小説の舞台は、こんなふうに設定されている。

折りたたみ北京(由郝景芳 - http://img.didixs.com/uploadfile/att/forum/201604/30/0858320yy1vknfj1yb2vgk.jpg,合理使用,https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5423681)

──折りたたみ式の街は三つのスペースに分かれている。片面は第一スペースで、人口は五百万人。彼らに割り当てられた時間は、午前六時から翌朝六時まで。その後、第一スペースは眠りにつき、地面が回転する。

裏面は第二スペースと第三スペースだ。第二スペースの人口は二千五百万人で、割り当てられた時間は二日目の午前六時から午後十時まで。第三スペースは五千万人が暮らしていて、午後十時から午前六時までの時間が割り当てられている。そして第一スペースに戻る。時間は慎重に分配され、各スペースの人々を完全に分離している。五百万人が二十四時間を享受し、七千五百万人が次の二十四時間を享受するのだ。

(大谷真弓訳、ケン・リュウ編『折りたたみ北京』[早川書房、2018]237頁)

比較的新しい本作品が興味深いのは、先述のオニール型コロニーという外宇宙で複製された生環境を、今度は地球内の都市空間に持ち帰って応用し展開した点である。本論ではこれまで、SF史の発展が外宇宙、内宇宙、電脳空間という三段階に分類できることを指摘したが、『折りたたみ北京』のこの発想は、さらにその先へ飛躍する時空間であり、生環境構築史における構築4を想像する手がかりとなるものかもしれない。

たつみ・たかゆき

1955年生まれ。アメリカ文学研究。SF批評。慶應義塾大学文学部教授。主な著書=『サイバーパンク・アメリカ』(勁草書房、1988)、『現代SFのレトリック』(岩波書店、1992)、『ニュー・アメリカニズム──米文学思想史の物語学』(青土社、1995)、『メタファーはなぜ殺される──現在批評講義』(松柏社、2000)、『アメリカン・ソドム』(研究社、2001)など。主な共訳書=『サイボーグ・フェミニズム』(共訳、トレヴィル、1991)など。

1. Three Stages of SF History: Outer Space, Inner Space, and Cyberspace

The history of science fiction begins in fairly straightforward fashion. The forerunner of the genre was Frankenstein (1818), by the British novelist Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, which served as inspiration for the American writer Edgar Allan Poe, France’s Jules Verne, and England’s H.G. Wells. In the early 20th century, Hugo Gernsback, an American engineer who had emigrated from Luxembourg, launched Amazing Stories, the first SF magazine, and established SF as a genre. Since 1953 the annual Hugo Award, which honors him as the “father of science fiction,” has been considered the ultimate quality-assurance label for contemporary SF works. Of course, if Gernsback was SF’s father, then Shelley, Poe, Verne and Wells must be considered its grandparents.

But how should we summarize the history of SF since then? It might be simplest to describe it as passing through three stages. The first, which extended from the 1920s through the “golden age” of SF in the 1950s, was dominated by stories about outer space. To get a quick sense of this stage, consider the triumvirate of writers most associated with its golden age: Isaac Asimov, who wrote the Foundation trilogy, Arthur C. Clarke of 2001: A Space Odyssey fame, and Robert A. Heinlein, author of Starship Troopers. SF in this period was truly “science fiction,” or perhaps more accurately “future-predictive fiction.” Figures like the legendary SF magazine editor John W. Campbell espoused an unquestioned faith in the process of extrapolation into the future from the data of the present.

In the 1960s SF entered a second, revolutionary stage known as the New Wave, fomented by British writers like J.G. Ballard, Brian Aldiss, and Michael Moorcock. Around this time the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in a dead heat in a space race launched by U.S. President Kennedy’s “New Frontier” manifesto. In response, Ballard et al., who were basically anti-Americanist in outlook, argued that what the world needed was an exploration not of outer but of “inner” space—i.e., the world of the subconscious. In Ballard’s The Crystal World (1966) and other works in his “catastrophe” tetralogy, he introduced elements of psychoanalytic theory, Dada/Surrealist poetics, countercultural thought, and the ideal of the “global village” envisioned by Marshall McLuhan and other media theorists. Ballard himself moved into the realm of “technological landscapes” in which technological space transforms into a new kind of Nature.

What is of interest here is that these New Wave writers redefined “SF” as standing for “speculative fiction,” a direction that three Americans collectively dubbed the “3Ds”—Thomas Disch, Samuel Delaney, and Philip K. Dick, author of the story on which the film Blade Runner was based—pursued to great acclaim. Not to be forgotten is the Polish writer Stanislaw Lem, whose masterworks Solaris (1961) and The Invincible (1964) initially appear outer space-oriented, but prove instead to be intense explorations of inner space. Because Lem’s portrayals of extraterrestrial intelligence consistently deviated from the anthropomorphic model, the Russian editions of his works were subjected to censorship. Nonetheless he persisted in delving into the inner space of Earthlings, albeit against a backdrop of alien planets. This was truly speculative fiction that has earned Lem accolades as a literary giant on a par with Kafka, Borges and Nabokov. The concept of the planet Solaris revolving around twin suns, which Lem came up with during the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, has something in common with the notion of the solarization of Jupiter that appears in Clarke’s 2010: Odyssey Two (1982) and Sakyo Komatsu’s Sayonara Jupiter (1983). In those works the concept is associated with dreams of an extraterrestrial utopia. More recently, however, that has morphed into the dystopian vision in Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem (2008) of a planet suffering from the presence of not two, but three suns.

At first glance the New Wave of the 1960s may seem to resemble a resurgence of modernism. However, the New Wave movement embraced a considerable number of women writers. Feminists like Britain’s Pamela Zoline and America’s Ursula K. Le Guin, as well as Canada’s Judith Merril, who not only wrote stories but was also an ardent New Wave polemicist and anthologist, were stalwart exponents of SF as speculative fiction. We should also note that Le Guin’s Hugo-winning The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) explores androgyny, that SF writer Alice Bradley Sheldon employed the synonym James Tiptree Jr., and that the aforementioned Disch and Delaney were both gay—so within the context of inner space it may be said that “gender space” in particular came to the forefront in the 1970s.

The 1970s also saw the advent of the Internet and the personal computer. In 1984, the South Carolina-born Canadian writer William Gibson’s debut novel, Neuromancer, introduced a new setting based on these technologies, cyberspace (a term he coined), thereby launching the cyberpunk movement. Gibson’s friend Bruce Sterling assumed the role of de facto spokesman for the movement, whose participants included John Shirley, Lewis Shiner, Pat Cadigan, and Rudy Rucker. Through their active promotion of the genre through co-authorship and anthologies, they established cyberspace—a realm that was neither outer nor inner space—as a legitimate new frontier. Their post-cyberpunk heirs include the British writers Richard Calder and Ian McDonald beginning in the late 1980s, and Japanese writers Goro Masaki in the 1990s and Project Itoh in the 2000s. Leading 21st-century SF writers like Australia’s Greg Egan and the Chinese-American Ted Chiang may also be said to follow in their footsteps.

To be sure, members of Japan’s third generation of SF writers, such as Chohei Kanbayashi and Mariko Ohara, had already been producing work that was essentially cyberpunk in the early 1980s. If we consider the international recognition enjoyed by works like Katsuhiro Otomo’s manga Akira (1982–90) and the animated film Ghost in the Shell (1995) directed by Mamoru Oshii and based on the manga by Masamune Shirow, we might find in this simultaneous global outbreak the first stirrings of the Cool Japan trend that caught on in the 21st century. Another offshoot is biopunk, which adopts an ecocritical stance in response to the Anthropocene era of global warming. A pioneer in this genre is Paolo Bacigalupi’s Hugo-winning novel The Windup Girl (2009), which caused a stir with its exploration of the possibilities of building a habitat (set in the story in an inundated near-future Thailand) that runs on energy generated not by steam or electricity or nuclear power, but by manually-wound springs.

2. News from the Frontier: From Terra Incognita to Terraforming

Looking back at the history of SF as we have summarized it here, we can see a pattern emerge, in which a prevailing frontier spirit spurs the exploration and development of diverse forms of “terra incognita” while also feeding back to contemporary civilization. Indeed, the man-made creature in Shelley’s Frankenstein vanishes in the then-unexplored Arctic, and the final scene in Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1837) takes place in the equally unknown Antarctic. The latter’s referencing of the theory of the Hollow Earth, which proposed the existence of an entrance to the planet’s interior at the South Pole, is significant for its influence on Jules Verne, as seen in his Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) and The Sphinx of Ice (1897). Poe himself got the idea from the Hollow-Earth tale Symzonia (1820), written by John Cleves Symmes Jr. under the pseudonym Captain Adam Seaborn. This book describes in great detail Symzonia, a peaceful kingdom of white people that exists at the center the Earth, free from war and illness because those who exhibit evil tendencies are banished to the surface, where they have run rampant. It is not hard to imagine how this utopian vision impressed Poe, who revered the white aristocratic society of the American South. Indeed, in its description of the lifestyle of the Symzonians, this book depicts a living environment that constitutes a direct critique of civilization on the planet’s surface.

Subsequently, and particularly just before and after the Civil War, the United States embarked on its Westward Expansion, spurred by the ideology of manifest destiny. By 1890 there were no more frontiers in North America. Still, the frontier spirit lived on.

Percival Lowell, an upper-class “Boston Brahmin” who had also spent time in Korea, arrived in Japan in 1883. His studies of the country yielded a book, The Soul of the Far East (1888), that influenced Lafcadio Hearn among others. His next obsession after Japan, however, was the canals of Mars, and his book Mars (1895) served as inspiration for The War of the Worlds (1898) by H.G. Wells, one of SF’s grandfathers. During his sojourns in Japan and elsewhere Lowell was a careful observer of the distinctive traits of people in the Far East. In the case of Mars, on the other hand, his belief in the existence of canals persuaded him that intelligent life existed there as well. In other words, the canals were proof of Mars as viable habitat.

Although Mars is only about half the size of the Earth, its surface area is nearly the same as that of the terrestrial continents. What is more, its rotation period of 24 hours, 37 minutes is virtually identical to the Earth’s. Granted, it takes Mars 1.88 times as long as the Earth to complete a revolution around the sun, making its seasons nearly twice the length of ours. All in all, however, Mars would be a nearly ideal destination for a migration of Earthlings—but by the same token, if Martians were compelled for some reason to abandon their planet, the Earth would be an ideal, and eminently colonizable, habitat for them too.

Wells’s portrayal of the Martians cemented the stereotype of aliens as invaders who looked like seafood—octopi, squid, shrimp, crabs. The turn of the century was accompanied by a succession of wars—the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese—in which Japan emerged victorious. These events further spurred a Western fascination with Japanese culture that took the form of Japonisme, even as apprehensions over a newly aggressive Asia sparked fears of the Yellow Peril. It was an era thus dominated by an exoticist blend of both admiration and fear of the Other. In any case, any fears of Martian invasion were put to rest by evidence obtained from the U.S. Mariner Mars probes launched between 1965 and 1973, and the Viking 1 and 2 landers in 1976, which indicated that the planet was devoid of seas or life, let alone canals.

Having dreamed of Mars for so long, though, the collective SF imagination is not about to stop going there. Works continue to proliferate that depict human efforts to make the planet habitable, using the latest knowledge to transform its environment into one like Earth’s. The American writer Jack Williamson first coined the word “terraforming” in 1942 to describe the process of terrestrializing a planet; since then contemporary SF giants like Clarke and Heinlein, and a bevy of other British and American writers like Greg Bear, Terry Bisson, Robert Forward, and Ian McDonald, have turned out terraforming-themed works. The apotheosis of this trend is the trilogy of Mars-SF masterworks by American writer Kim Stanley Robinson, Red Mars (1993), Green Mars (1994), and Blue Mars (1996).

3. The Monolith’s Prophecy: 2001 as a Microcosm of SF History

From this account it should be apparent that the outer-space orientation of SF’s first stage developed as a sort of blending of the Mars boom with turn-of-the-century Oriental exoticism. The inner-space orientation of the second stage gave birth to surrealistic renderings of end-of-the-world scenarios that seemed to critique the era of high economic growth and raised alarms over such ecological threats as nuclear testing and global warming. The cyberspace of the third stage in no time became the everyday reality of contemporary society, and its antiheroic computer hackers were the prototypes of today’s cyberterrorists.

Our reading of SF history suggests that the Clarke-Kubrick collaboration 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was released in 1968, a year before Apollo 11 landed on the moon, encapsulates the past, present, and future of that history in a single work. In this respect it can be linked to the history of habitat building as well.

The mysterious monolith that aliens placed before subhuman primates living on the Earth four million years ago (three million years in the novel) was a teaching tool, a catalyst for the evolution of the human species. But when a similar monolith is discovered on the Moon at the dawn of the 21st century, it emits a bizarre noise: this monolith is a communication tool for informing the aliens of the level attained by human civilization. Then, as the spaceship Discovery One approaches Jupiter (Saturn in the novel) with the supercomputer HAL 9000 on board, the computer goes berserk, the ship is cast adrift, and Captain Bowman encounters a huge third monolith near Jupiter, a “star gate” that sucks him into a kind of hyper-space-time that replicates the stars themselves and subjects Bowman to a hyper-evolution of his own.

I would like to draw your attention to the fact that the three monoliths correspond to the three stages of SF. The first monolith is a colonialist teaching device dispatched to foster the evolution of intelligent life in outer space. The second monolith is a communications device that serves as a medium for interconnection with the inner space of humanity. The third monolith is nothing if not cyberspace itself, a space capable of replicating the world, and analyzing and reconstructing human bio-information. The three stages of the monolith thus perfectly mirror the history of contemporary SF.

What is significant here is that Clarke configured aliens not as Wellsian imperialistic invaders but as “farmers in the fields of stars.” These aliens, who intervene to accelerate the evolution of intelligent life wherever they find it sprouting in the universe, had themselves abandoned their physical bodies to house their minds and thoughts in metal and plastic. Then, having discovered a way to store their knowledge in space and their thoughts in light, they transformed into pure energy and now traverse space freely as “lords of the galaxy.” This concept has inspired countless imaginings of humanity evolving into bodiless software that makes cyberspace its habitat—prime examples being Greg Egan’s Diaspora (1997) and the Wachowskis’ Matrix trilogy (1999–2003).

However, the one work that has most faithfully adopted Clarke’s notion of alien meddling in human evolution, not as a hubristic colonialist project but as a sort of farming, is the film Interstellar (2014) directed by Christopher Nolan. In a plotline that echoes Nobel Literature Prize-winning novelist John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939), farmer Joseph Cooper leaves the Earth as a blight destroys all its crops, and searches outer space for an ideal planet to move to. But when he tries to return home via a wormhole, he winds up in a four-dimensional structure that somehow recalls Borges’s Library of Babel and seems to have been built by aliens, in which he transcends space and time. It turns out the builders of this monolith-like structure were not aliens but future humans. Cooper is rescued and awakes in “Cooper Station,” a utopian habitat in an O’Neill colony which his daughter, left behind by him on Earth but now an eminent scientist, has built in orbit around Saturn. He finds that the Cooper farm he left on Earth has also been reconstructed there.

In some respects this is a simple and straightforward narrative, but at the same time it is radical. Firstly, it introduces “aliens” who are not the Hollywood stereotype of malevolent invaders from another planet, but humans of the distant future who have overcome the confines of flesh and blood—post-humans if you will. Secondly, it suggests that humanity’s desire to explore outer space may itself be the result of the habitat-building undertaken by “farmers in the fields of stars.” There are many ways to view the work: as a critique of the traditional SF image of outer-space conquest, as a concept that points toward Habitat Building Mode 4, and as a vision that expands, from a critical perspective, on the issues raised by Clarke and Kubrick over half a century ago.

4. Conclusion: Hao Jingfang’s Folding Beijing

Finally, I would like to conclude by mentioning Folding Beijing (2016), the novella by the renowned Chinese SF author Hao Jingfang. This Hugo-winning masterpiece vividly describes the dynamics of a time-sharing system under which citizens of different class-based sectors of a city take turns using the same urban space. At a specific time of day, a designated class is rotated from underground to the surface while the class previously occupying the surface is rotated back underground. This work is, I am convinced, the most closely linked to a vision for habitats of any written today. The setting of the story is as follows:

The folding city was divided into three spaces. One side of the earth was First Space, population five million. Their allotted time lasted from six o’clock in the morning to six o’clock the next morning. Then the space went to sleep, and the earth flipped. The other side was shared by Second Space and Third Space. Twenty-five million people lived in Second Space, and their allotted time lasted from six o’clock on that second day to ten o’clock at night. Fifty million people lived in Third Space, allotted the time from ten o’clock at night to six o’clock in the morning, at which point First Space returned. Time had been carefully divided and parceled out to separate the populations: Five million enjoyed the use of twenty-four hours, and seventy-five million enjoyed the next twenty-four hours. (English translation by Ken Liu)

What is especially intriguing about this relatively recent work is that it takes the aforementioned O’Neill colony concept of a habitat replicated in outer space and applies it to a terrestrial urban space. In this essay I have argued that the history of SF can be classified into three stages: outer space, inner space, and cyberspace. However, Folding Beijing represents a further stage of space-time, and as such it may offer clues toward the imagining of Habitat Building Mode 4.

Takayuki Tatsumi

Born in 1955. Professor of Literature at Keio University, researcher on American literature, and SF critic. His major works include Cyberpunk America (Keiso Shobo, 1988), Rhetoric of Contemporary Science Fiction (Iwanami Shoten, 1992), New Americanist Poetics (Seidosha, 1995), Metaphor Murders (Shohakusha, 2000), and American Sodom (Kenkyusha, 2001). He also edited and co-translated Cyborg Feminism (Treville, 1991).

(Translation by Alan Gleason)

- 生環境構築史とSF史:基調講演

-

Habitat Building History and History of Sci-fi: Keynote Speech

/生環境構築史与科幻小说:主旨演讲

巽孝之/Takayuki Tatsumi - 生環境構築史とSF史:座談

-

Habitat Building History and History of Sci-fi: Discussion

/生环境构筑史与科幻作品史・座谈

巽孝之+生環境構築史編集同人/Takayuki Tatsumi + HBH Editors - 地球の住まい方──ジュール・ヴェルヌ〈驚異の旅〉における「ロビンソンもの」の展開

-

Verne’s Never-ending Voyages

/地球的居住方法——儒勒・凡尔纳《奇异旅行》系列中的“荒岛文学”情节

石橋正孝/Masataka Ishibashi - 中国SF小説においての現実と非現実──「科幻現実主義」と劉慈欣の作品から語る

-

Reality and Non-Reality in Chinese Science Fiction

/中国科幻小说中的现实和非现实: 从科幻现实主义作品和刘慈欣作品出发

藤野あやみ/Ayami Fujino - 退屈な都市と退屈なSF、過去に語られた未来から逃れるために

-

The future is going to be boring

/无聊的城市、无聊的科幻,为了逃离过去所描绘的未来

樋口恭介/Kyosuke Higuchi - エイリアンのアヴァンガーデニング

-

Alien Potatoes

/外星先锋园艺

永田希/Nozomi Nagata - がれきから未来を編む──災間に読むSF

-

A Science Fiction Survival Guide to Doom and Destruction

/从瓦砾中编织未来──在灾难的间隔之间阅读科幻小说

土方正志/Masashi Hijikata

協賛/SUPPORT サントリー文化財団(2020年度)、一般財団法人窓研究所 WINDOW RESEARCH INSTITUTE(2019〜2021年度)、公益財団法人ユニオン造形財団(2022年度〜)